It’s Noon in Israel: The Opposition: Six Drivers and No Directions

Also, Bibi might not need the pardon, and the strange political alliance protecting Israel's black market.

Blue and White chairman Benny Gantz, Ra’am leader Mansour Abbas, Yisrael Beiteinu’s Avigdor Liberman, and The Democrats leader Yair Golan. (knesset.gov)

It’s Sunday, February 15, and four months have passed since the return of the hostages and the declaration of the end of the war in Gaza. Eighty-six polls have been published since then. All but one show that the “change bloc” does not have 61 seats—the majority required to form a stable government without rotation with Netanyahu and without favors from the Arab Ra’am party’s chairman Mansour Abbas.

As many party leaders as there are, so too are the answers to the question: “How will you form a coalition?” Blue and White head Benny Gantz proposes unity with Likud; Democrats chairman Yair Golan proposes a recreation of Bennet’s 2021 government, uniting with the Islamist Ra’am party. You already know Yahsar! Chariman Gadi Eisenkot’s “58-plan.” Yisrael Beitinu’s Avigdor Liberman repeats like a mantra the number “63,” hoping somehow the bloc will reach it.

And Naftali Bennett? Here the answer splits in two. One part hints that Religious Zionism could join such a government, making Abbas unnecessary. The only problem is that the same thing was said after the 2021 election—and Smotrich, unfortunately, did not connect to the idea. The second part is a kind of parity unity government. Bennett has said there is no mandate to sit with the Arabs, but has not made a similar commitment regarding Likud. That is a substantive shift: like Gantz, it implies a government with Netanyahu. Not as a fifth wheel, as Blue and White once proposed, but like in a driving lesson—two steering wheels in one car.

The clearest evidence that the change bloc has internalized the new electoral reality is the flood of budget-heavy initiatives in the Arab sector: a “day of disruption” (one really wonders where the idea of blocking the highway to force change came from) and massive voter-mobilization campaigns now being built for the election.

If the goal is to achieve 61 Zionist votes, massive Arab turnout is a catastrophe. If the goal is to block Netanyahu from reaching 61, encouraging turnout in the Arab sector is the order of the day.

The reestablishment of the Joint List was not Bennett’s initiative—quite the opposite. But the assumption is that this many-car train has already left the station, and there is no point fighting it.

The next test will nevertheless come: what will Netanyahu and his opponents do when a proposal is brought to disqualify the Arab party Balad from running for the Knesset? This is a party with a rich record of support for terrorism or partnership in it by its senior members. Disqualifying it could reduce Arab willingness to vote. In the last election, neither Likud nor Yesh Atid took a clear stand: Netanyahu wanted Balad to waste votes; Lapid feared angering Arab voters. The fate of the fanatic faction now depends on the polling numbers toward the end of the summer.

This is an excerpt from my weekly column in Israel Hayom.

Benjamin Netanyahu holding a cabinet meeting in 2010 with former Attorney General Avichai Mandelblit and then Military Secretary, Eyal Zamir. (Amos Ben Gershom/GPO).

Of all the attacks to come out of the meeting between Netanyahu and Donald Trump last Thursday, Israeli President Isaac Herzog was not the target I expected. After Trump said Herzog “should be ashamed of himself” for not granting Bibi a pardon, Herzog hit back forcefully: If Bibi had requested this attack, the pardon is off the table. Bibi denied it, and I am inclined to believe him. Bibi is famous in Israel for his understanding of the presidency; asking Trump to deliver an attack without predicting the backlash would be a serious lapse in judgment.

But if this was Bibi’s attempt to interrupt the legal process, it wouldn’t be the first questionable part of the proceedings. Last week, a question was asked that could free Netanyahu from his indictments on grounds of improper process.

In the “gifts” case, did the attorney general approve the investigation into cigars and champagne, as required by law or not?

The prosecution insisted he had, but it seems that Bibi was a tangent rather than the focus of the investigation. The attorney general had approved investigating the “iceberg”—a large-scale gifts-and-money operation involving businessmen. When Bibi became the target, former Attorney General Avichai Mandelblit expressed shock that the police had exceeded their mandate:

“You are now starting a completely different investigation, exactly into things I did not approve,” he rebuked them.

That put the prosecutor—who denied the existence of such statements and attempted to prevent their publication—in an awkward spot, especially after she claimed:

“The prosecution reviewed the protocols from the relevant period held at the attorney general’s office and did not find the ‘quote’ attributed in the publication.”

But Mandelblit was part of the proceedings; wouldn’t the quote have come up in his testimony?

Well, he did something more sophisticated than outright denial: he told the truth—but only part of it. In his affidavit for the case, he wrote that “I approved most of the substantive investigative actions taken in the cases”—most, except one: opening the investigation in the most significant case against the prime minister.

Of all the alleged offenses in the Netanyahu cases—witness coercion, fabrication of evidence, concealment of others—this is the most significant. The judges already have before them a request to dismiss the indictments on grounds of abuse of process. But the panel is intimidated. They endured a torrent of abuse when they expressed doubts about the bribery charge and have been cautious ever since.

Taken together with Herzog’s response, it seems Netanyahu’s legal troubles are far from immune to pressure—foreign or domestic.

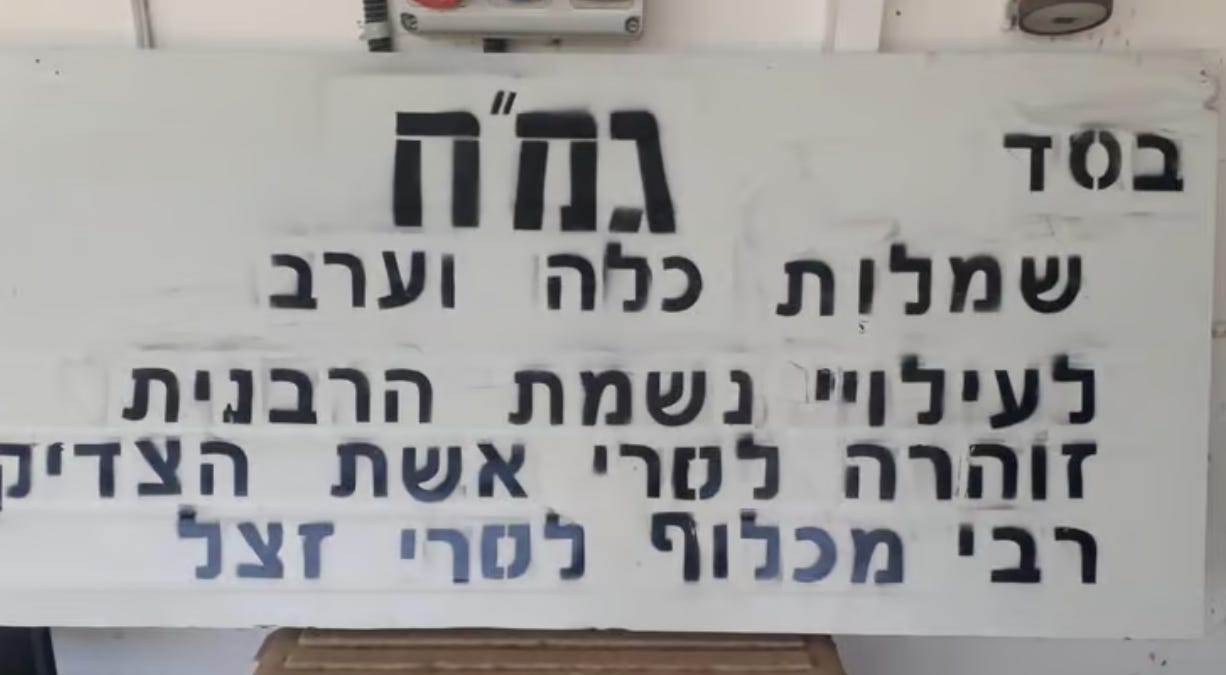

A sign for a Gmach reading “Gemach —wedding and evening dresses” (Boi Kalah Gmach)

Don’t take this as advice—but in theory, if weren’t a fan of taxes, in Israel you could take a large check, walk into a money changer, and walk out with cash minus a modest commission. Not your style? Well, you can “donate” a generous sum to a friendly gemach (free-loan society), and that donation will find its way back to you in cash with a small contribution deducted, of course.

Everyone’s happy—except the Tax Authority.

A new law making its way through the Finance Committee is seeking to plug this loophole that loses the state an estimated billion shekels in tax revenue annually. The proposal would prevent these large-scale currency exchanges by limiting cash transactions to 6,000 shekels and would prohibit businesses holding cash sums exceeding 200,000 shekels.

Protecting this system is one of Israeli politics’ stranger—though hardly rare—alliances: Haredim and Arabs. In this case it’s simple: both communities have sizable cash economies, and neither is especially enthusiastic about taxes.

It’s kind of funny. Israel may be heading into an election that the Haredim or the Arabs could decide, and yet they may have more in common with each other than with their respective coalition partners.

If you enjoy the newsletter, you can show your support by becoming a paid subscriber—it really helps keep this going. I’m also offering a special monthly briefing for a small group of premium members. I’d love to have you join us—just click below to find out more.

Sunday February 13th?