Mossad Kidnaps Ex-Lebanese Security Official

Also, Army Radio officially disbanded by the cabinet, Israel’s media suppression law extended, and more.

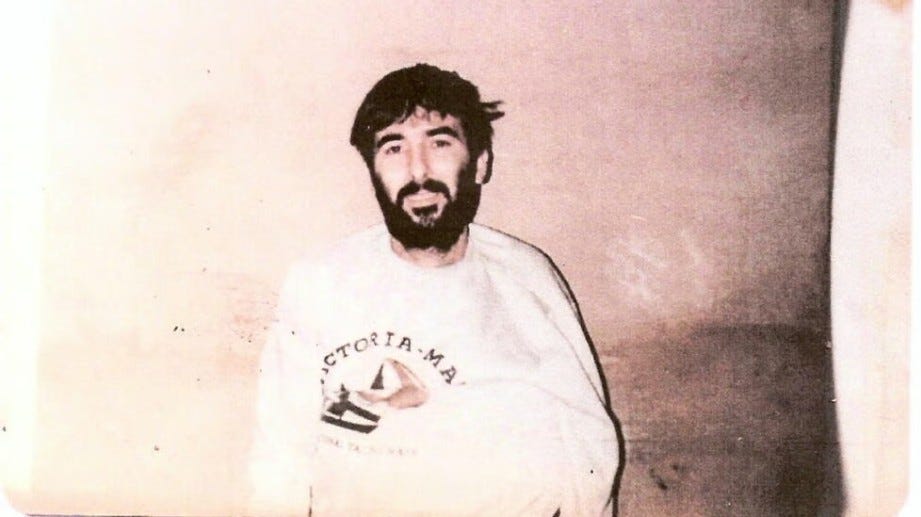

Ron Arad

It’s Wednesday, December 24, and the Mossad has been busy in Lebanon. According to the Saudi paper Al Arabiya, Israeli agents abducted an ex-Lebanese security official, Ahmed Shukr.

You might recognize the last name. He’s the cousin of Fuad Shukr—Hezbollah’s chief of staff, the man who had a $5 million bounty on his head until he was taken out by…