Somaliland Recognized: What’s in it for Israel?

Also, clarifying QatarGate, and the grim reality of Palestinian Christmas.

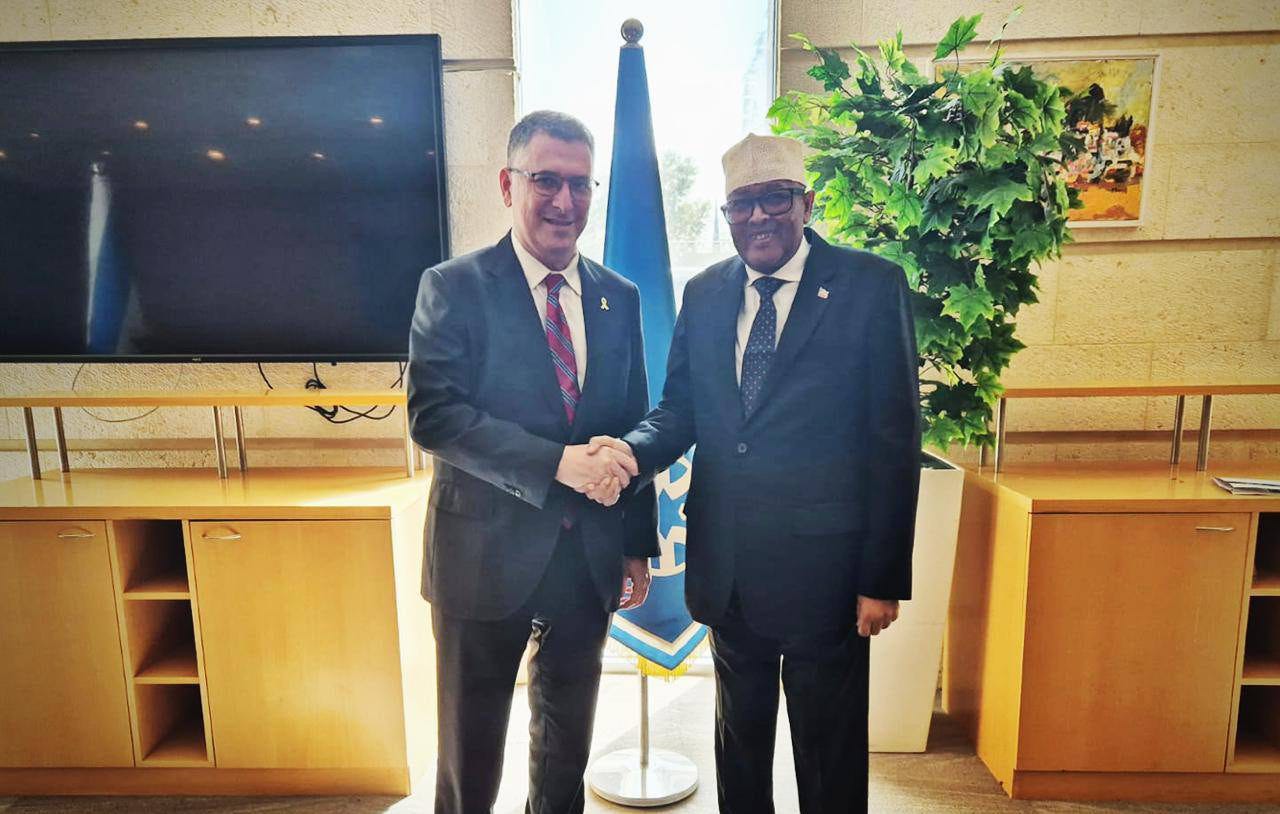

Somaliland’s President Abdirahman Mohamed Abdullahi and the Israeli Foreign Minister Gideon Sa’ar. (Israel Foreign Ministry)

It’s Sunday, December 28, and people seem to have short memories. When Israel recognized Somaliland this past Friday, you could practically hear the question being asked: “What’s Somaliland?”

That’s the second time this year. The fi…