Venezuela Was First Will Iran Be Second?

Also, the three men who made Israel’s current politics, and the challenges facing the economy in 2026.

Also, the three men who made Israel’s current politics, and the challenges facing the economy in 2026.

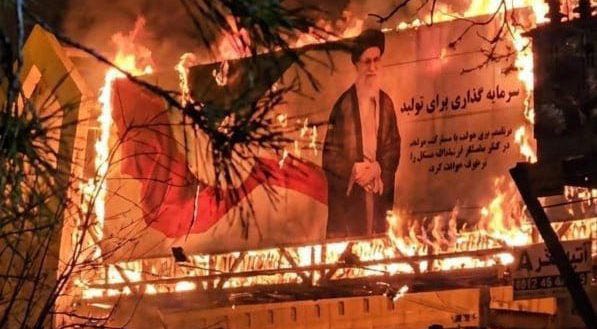

A bilboard of Ayatollah Ali Khamene burning in Iran yesterday.

It’s Sunday, January 4, and in the popular Netflix series Squid Game, the very first challenge is a childhood classic: Red Light, Green Light. Players are told they have five minutes to cross…